The Ronart W152

Well, Arthur Wolstenholme (the designer) will tell you…

“It was conceived in 1981 following a visit to the Daimler-Benz museum in Stuttgart, Germany, and then it went into production in 1986. The cars that influenced the design of the road-legal W152 were the Mercedes W154/196, the Maserati 250F, the Vanwall, and the HWM Jaguars of the time. Continual development has resulted in what the Press and owners consider to be the closest interpretation of a typical racing car of the 1940’s/1950’s.”

Arthur hit the lampost later

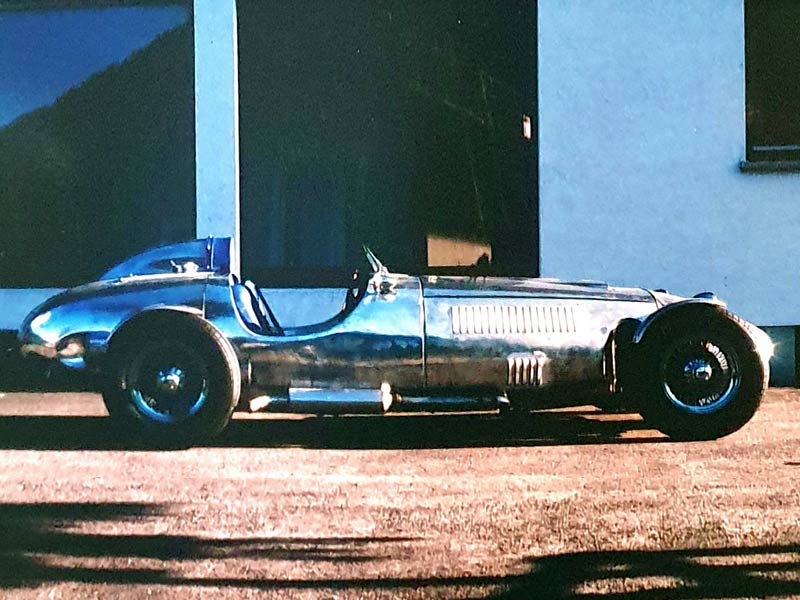

The Official Photo This prototype, Chassis No. 001, is the one you might have test driven if you visited the factory in Peterborough.

We will tell you…

“It is a serious piece of machinery designed for Jaguar lovers (Mk.I & Mk.II Jag-powered versions) who want to feel the wind in their hair. The styling leaves everything else for dead.”

The Ronart W152 is a British, hand-built, high-performance two-seater sports/racing car suitable for use on road or track. It reproduces the classic style of the front-engined Grand Prix cars, and combines today’s performance with reliability, safety and advanced composite materials. It is supplied fully built by the factory but has also been available in the past in component-form for the enthusiast to build at home.

Prior to 2000 there was a choice of engines from the popular 4.2 litre straight-six Jaguar XK series engine, the 3.8 litre XK engine, the 4.0 litre AJ6, to the 5.3 litre V12.

The original chassis design and fabrication was entrusted to Spyder Engineering, a company highly acclaimed for its association with Lotus Cars and racing activities since the 1960’s. The Mk.II was announced in 1997 and from then on the chassis was built at Ronart Cars. This chassis is a multi-tubular backbone spaceframe which is sandblasted and primed with self-etching primer which bonds the paint firmly to the bare metal surface. A coating of enamel is applied and baked, to give a hard and durable finish. The bottom-line is that it just doesn’t corrode.

Chassis No.002 The first production car built by Patrick Smith in 1987. Launched at Classic Car Show 1988.

The MkI once owned by Mike Kanter

Chassis No. 054. The first Mk.II built by Craig Winstanley in 1997.

The body was available in a choice of 3 material options –

- Glass reinforced fibres (GRP)

- Carbon-Kevlar & glass reinforced fibre composite

- Aluminium alloy

The car could be finished in any colour and many trim options.

The donor car for most of the other bits and pieces (Mk.I & Mk.II models) was typically a Jaguar Series II XJ6 which could be acquired for a few hundred pounds. This provides the suspension (front & back), gearbox, brakes, instruments, etc.

To read some more about the early years, including an interesting advert, and an illustrated review of the W152 Mark I by David Hill of Component Car Magazine click here.

OK, but what will it do?

Well, the performance is adequate, but if you are influenced by these things, 0-60 in about 6 seconds (XK Straight Six), and a top-end dependent upon engine, gearing, and what your face can bear.

Roger Cook reviews and road-tests the Ronart W152 Mark II on TV’s Pulling Power programme.

…or Mysterious Maserati, False Ferrari or Imitation Itala. The Ronart W152 is the car you want it to be, as David Hill discovered.

(Reproduced from Component Car magazine. March 1989.)

Despite the aeroscreen, the flies stung like fury as they met their sudden end, their shattered remains mingling with those of their predecessors in the mask of oil and grime covering my face. Steel, blood and bone sped on at an insane pace as the two machines, their drivers urging them on as much by willpower as with skill, vied for supremacy at the last bend.

The bulbous tail of the blood red Ferrari rose a fraction as the brakes bit, the open exhaust spitting defiance at the closure of the throttle. This was my signal. Casting loose from the slipstream’s pull, I swung the car’s silver nose towards the inside. Foot down, snake, correct, drift… I was through and charging hard for the Finish. The welter of passing images held the memory of a momentary swoop of black and white checks. Onward to victory, champagne and the winner’s laurels.

The ability to weave such dreams is a rare quality in anything, let alone a mere means of transport, but the incredible Ronart had that ability down to a fine art. The day on which I tested the car was one of those during which the percentage of successful events is balanced by an equal percentage of opposing forces. Support cars broke down, people lost each other in transit; that sort of thing. Thus, schedules went awry, leading to test conditions that were less than ideal.

When I finally got around to driving the Ronart, it was late. The lateness of the hour, not to mention that of the season, meant that the temperature was well on the wrong side of zero, making black ice more than likely to be encountered. Also, it was pitch dark. By my reckoning, testing the ability of the Ronart to bounce off the scenery whilst in a zero grip slide was just a little beyond the call of duty. So the insane pace was, in fact, about 60 mph. The blood red Ferrari was a wayward Metro and the final curve was a roundabout somewhere outside Peterborough. Still, although the Ronart could not be tested either to my satisfaction or to your, it still had that magic quality. Let me explain why.

If you were to meet Arthur Wolstenholme socially, it would come as something of a surprise to learn that he produces such a car as the Ronart. The same goes for his wife Rona who, apart from making up 50% of the car’s name, plays a major part in the business, and is a dispenser of medicines to boot. Arthur himself is a RAF trained electronics engineer, a profession that he continues to pursue. Their house, with the exception of a few pictures, is devoid of the automotive trinkets usually encountered; in general, no clues to the way in which the Ronart project came about are to be found. However, judging books by their covers is a profitless occupation, the adage proven by that that came to light as the story unfolded.

In 1981, Rona and Arthur had a continental holiday, during which they visited the Mercedes Benz museum at Stuttgart. Arthur, studying the early racing cars on show there, wondered what it would be like to drive such a machine on the road. The Ronart was conceived with that thought and, on returning home, Arthur started to sketch. Naturally, the car would have to be a two-seater, for Rona’s benefit. And an initial design, complete with doors, was arrived at. 1984 saw the arrival of a dog-eared XJ12 in the Wolstenholme household and armed with the proposed body’s dimensions and a pile of parts mechanical, Arthur set about marrying the two with a chassis.

This was a box-section steel structure following a basic ladder pattern, put together in the garage with an arc welder. The string and chalk mark method brought together a chassis worthy of the name, but one which was neither pretty nor particularly efficient in terms of ration of strength to weight. Putting it bluntly, it was crude, and the pedantic Arthur wasn’t happy with it. But during this exercise, potential markets for the project had been studied, with the initial target being the classic car enthusiast. The concept was unique and apparently saleable, and so the decision to go into some serious development was taken.

In January 1985, Spyder Engineering was commissioned to put together a chassis suitable for V12 power and, at Arthur’s home, work started on a jig for an all-alloy body. The results of both these actions met up a few weeks before the NEC Motor Show in May, and the car made its debut there as a visual concept. The feedback from this appearance was tremendous, despite the car’s partially complete state. The public was taken aback and there were members of the Jaguar Drivers Club who were convinced that it was the Indianapolis Lister Monza car. On the second day of the show, the owner of that unique vehicle came over to the stand in a state of concern; he was worried that the Ronart was to be marketed as a replica of his car and needed a lot of reassurance that such a crime wasn’t to happen!

With exclamations of approval still ringing in their ears, Arthur and Rona took their car to the Kit Car Show at Newark. This appearance realised the possibility of marketing the Ronart as a kit car. The valid point was that, although the alloy body was a desirable commodity, the cost of producing it narrowed the market considerably. The existing body therefore served as a buck for a suit of clothes in GRP, the moulding work being carried out in the winter of 1985. The resultant body was mounted on the chassis for the 1986 Stoneleigh kit car show, and the car made a second appearance at the NEC shortly afterwards. By October the Ronart was roadworthy, and in November, five independent motoring magazines carried out tests. The Press were impressed and, encouraged by the response, Arthur continued the development work.

Over a 12-month period, a variety of spring rates and roll-bar thicknesses were experimented with, leading to a fully sorted suspension in the first production car which appeared in mid-1987. Earlier this year, the current production mould had been constructed, once again using the original body as a buck. The final result is lower, shorter and wider than the first GRP body, and countless hours of labour have brought about substantial improvements in the fit and finish of the panels. A number of potential customers drove the car, becoming actual customers in the process, so that 8 Ronarts now grace the Queen’s Highway, with a further 12 gracing the Wolstenholme order book.

The conclusion to be drawn from this history is simple. There has been a large amount of development, which is a costly process to say the least. The car could have been on the market in the early part of 1986. The fact that it wasn’t released until more than a year later proves that, in theory at least, the time and effort were taken to get the car right. Having encountered the fast buck approach in the past, I considered this painstaking approach to be praiseworthy. But would the Ronart live up to its on-paper promise? The investigation continued.

Arthur Wolstenholme and Victor Moore, director of Spyder Engineering are two of a kind. They are both men who know a great deal without making a noise about it. They let their work speak for them. This means the expectation of a highly finished product is a reasonable one.

Spyder’s experience in the manufacture of Lotus replacement chassis has been employed in the backbone item produced for the Ronart. This structure is well up to handling the power of the V12 and accommodating the straight-six XK engine is merely a matter of swapping mounting brackets. The chassis accepts Jaguar wishbones at the front, allied to Spyder’s own roll-bar and an MGB rack which makes use of extension couplers attached to Jaguar ball-joints. Spyder-developed steering arms are used which, like the optional Spyder front wishbones, are nickel plated to a fine finish. Apart from the visual aspect, this procedure makes any cracking easy to spot.

Jaguar’s independent rear suspension is attached to the chassis by metalastic bushed carrier plates, allowing the heavy and rot-prone Jaguar cage to be dispensed with. The only other modification is the attachment of special tie-bars which are sufficiently lengthy to avoid wind-up under cornering loads. Spyder also manufacture pedals and engine-mountings and those items which are not cadmium or nickel-plated are sandblasted, etch-primed and then given a baked enamel coating. The practical results are an excellent finish and a six-year anti-corrosion warranty.

One criticism of a backbone chassis is its lack of side intrusion protection. In the Ronart, shaped frames follow the body contour at the scuttle and rear bulkhead planes. Furthermore, each side of the cockpit is protected by a rail which is bonded into the body and bolts to the frames at either end. The complete structure is further employed in providing locations for the seat belts, pedals and steering column, and beneath the hump is a roll-bar extension to protect the driver’s head.

The rolling chassis is a relatively simple structure in itself. The comparatively light weight of the car allows the use of single rear dampers, and extraneous bracketry is conspicuous by its absence. The bodywork is formed in six sections, minimising the extent of replacement required in the event of minor crash damage. Space limitations dictate the use of a special radiator which employs a high-efficiency core capped with the original Jaguar tanks. A beautifully made alloy fuel tank is mounted in the tail protected by the rear-end hardware. The tank is fully baffled and is surmounted by a polished Aston-type fuel cap concealing the ‘real’ filler.

The braking system is transferred direct from the donor with the exception of the servo unit. The smaller Marina servo reduces the level of assistance to an amount suitable for the lighter Ronart, taking up less space in the process. The rearward siting of the engine necessitates a shortened propshaft which is available on an exchange basis. The associated extension to the steering column is provided in the shape of a bespoke steering shaft, while the magnificent exhaust system is also specially made but is not quite what it might seem.

A manifold and E-Type pattern silencers are made of mild steel. The pipes, wrapped in woven asbestos tape, live inside the flexible stainless covers which give the exhaust its visual impact. The punctured silencer cover is also in stainless steel. Inside the car, use is made of the Jaguar instruments and optional dashboards are available for XJ or S-Type clocks. The seats and trim are specialised items with the option of hide being available. Current weather equipment consists of a tonneau cover or alternatively a single-seat conversion panel in GRP. A wrap-around windscreen is currently being developed in perspex. A glass wrap-around screen and a hood and side-screen set will follow shortly.

A car such as the Ronart demands the use of wire wheels and these, and their associated hardware, are available from Ronart. Further traditional demands are satisfied by accessories such as a cast alloy spark-plug holder and spun alloy racing mirrors. Ronarts are available in left- or right-hand drive form and for the absolute purist, hand-made alloy bodywork may be specified. Part-builds are also undertaken upon request. Part-builds notwithstanding, the ease or otherwise of building a kit car is a major factor in its popularity.

A system of part identification for the Ronart has been generated with a computer. The result is a four-sheet list upon which each and every item is listed by description, size and quantity. Every single part has a reference number, that same number appearing on the bags and boxes in which the parts arrive. This has been done so thoroughly that, provided you can resist the temptation to open all the nags ta once, putting a Ronart together should be simplicity itself. Allied to this is a very comprehensive level of supply, down to the minutiae such as brake pipes, rack shims and battery clamps. The whole of the hardware is included in the kit, as are the siring loom and fuse box. The same goes for the special radiator and even the electric fan is included.

The advantage of this approach is a considerable one in that, given a good set of donor parts, no time need be wasted in motor accessory shops. It’s all there for you. The foregoing reveals the Ronart to be a desirable prospect in many ways. However, a manufacturer could go to the extent of including the paint in the kit and still not compensate for a basically poor product. This begs a question. How good is the Ronart in the flesh?

Visually I can think of nothing quite like it and if you like to be noticed this is the car to buy. The Ronart is also a sizeable device measuring 170″ from nose to tail, and standing back to take the car in as a whole requires a modicum of space.

A point that may be mooted is that the use of unmodified XJ6 suspension has dictated the overall size of the Ronart. Alternatively the generous legroom in the legthy footwells may be considered as either a cause or a result of the car’s size. What matters is that the car is proportionate, and if that makes it imposing, so much the better. The Ronart’s lines are curiously reminiscent of many different cars and according to Arthur, the colour used makes a big difference. Consequently, by sticking to the relevant national racing colour, you can have a reasonable representation of a Ferrari, a Jaguar, a Vanwall or whatever takes your fancy.

Unfortunately legal requirements must dictate a compromise in certain areas on such a car. Bolting lights and mudguards onto a racing car is bound to make it look odd, but it must be done. In the case of the Ronart, these items have been added in an unobtrusive way, and look as much at home as can be. Negotiating the low cockpit side to gain entry to the car was easy, only the bulk of the essential flying jacket hampering the entry procedure. Once installed, I found the cockpit comfortable despite the lack of carpets. Arthur had set the car up for himself but the position of the pedals in relation to the fixed seat was fine for me. Freaks of nature are provided for by a range of pedal fixing points, the use of which is a task requiring spanners.

The large, near-vertical wheel was sufficiently well spaced from both the dash and the driver to be comfortable and the side cutaway left plenty of elbow-room. The dash itself was a no-frills affair, with the required information and no more. Jaguar instruments were reasonably well-placed, with minimal masking by the wheel. The seats, dash and bulkhead roll trim was nicely done, although the tunnel trim was a touch wrinkly in places. The overall effect was simple, though not spartan, and therefore comfortable.

With the controls identified, I fastened the three-point harness and pressed the starter-button, to be rewarded by heavy churning noises from up-front. Next came the sort of sound which is capable of turning an enthusiast’s spine to jelly. The bark from the short side exhaust may not have been loud but it certainly sounded right with bags of basso profundo to be heard. The gearchange on the high tunnel too had a typically Jaguar feel as it was slotted (there is no other word) into first, and Arthur and I cruised forward into the cold darkness. At this point it was necessary to pass through an area used by adairy for the daily washing of their vehicles.

The concrete apron, which had be wet, was by now a solid sheet of ice and the start of the test consisted of mostly wheelspin. With this warning in mind, I set out onto the open road. The quality of the Ronart’s ride was noticed first, the rigid chassis and quality bodywork combining to give a supportive feel on the road. This created an immediate feeling of confidence and, with a long dual-carriageway to be used, the Hill hoof headed for the bulkhead. The reward for this action was a straight-six symphony accompanied by a firm push in the back.

The demonstrator was fitted with a 3.07 differential, giving a theoretical top speed of 180 mph! This tallness of gearing made its presence felt by reducing the acceleration from shattering to merely lusty. The 4.2 engine, breathing through triple 45 DCOE Webers on a Lynx manifold, was nevertheless fully capable of delivering the goods on demand and using the overdrive made top gear cruising a very relaxed procedure.

The numerous roundabouts in the area gave me the opportunity to explore the handling. The rearward siting of the engine gave the car a strictly neutral balance which, allied with the pin-sharp responses, made the Ronart more agile than might have been expected. In fact, given better conditions, I would say that flinging a Ronart through the bends would constitute one of life’s little pleasures. The controls offered a pleasing firmness, yet were light enough, I would image, for the ladies, given suitable modifications to the low seating position.

Driving the Ronart gives a unique view of the world, with seemingly yards of bonnet in front and a position knee-high to almost every other road user. The vision from the hot seat was good and the two scuttle-mounted mirrors gave a complete picture of event behind. When I enquired after heating facilities, Arthur gave me the sort of glance which suggests that great fairies are in mind. Despite that, a heater can be fitted, the Mini or Spitfire unit being the favourite choices. Apparently those Ronart owners who have a heater can be easily spotted: they’re the ones who are still grinning in sub-zero conditions.

Critics of the Ronart are apt to use the word ‘impractical’ with monotonous regularity. This is a reasonable enough view, although the recent innovation of a hingeing tail has provided a surprisingly capacious, if oddly shaped, luggage area. This apart, the Ronart must remain a superb cobweb-remover until the weather equipment appears. However, if your pocket will stretch to a car more suited to the Beaujolais Run than the weekly shopping trip, the Ronart is unparalleled in its appeal.

Two versions of the car are available, the S6 kit for the XK engine and the more obviously titles V12 kit. The basic body/chassis kit cost £2994 plus VAT in either case. The additional parts packs cast £3750 plus VAT for the S6 and £3950 plus VAT for the V12. The listed optional extras include such parts as seatbelts, tonneau cover, aeroscreens, wheel and hubs. Hide trim is also listed as an option to the standard leathercloth, with the possibility of mixing and matching trim materials to taste. Over and above the works items, you will need a donor, a set of tyres and an amount of paint,

These prices seem high at first glance. Whilst it is true that the Ronart is not a cheap kit, anyone who has had the experience of building a kit car will know how quickly the cost is boosted by those nuts, bolts and lengths of Aeroquip hose. If in doubt, try asking your local fabricator for a 6 into 1 exhaust in mild steel with stainless cladding. Furthermore, the inclusion of all the little brackets, painted and ready-to-use represents a valuable saving in man-hours alone. These, in common with the rest of the fabricated parts, are of the highest quality.

The comparatively simple nature of the Ronart’s construction would, I feel, make for an easy build and Arthur and Rona supply each builder with report forms to fill in, the aim being a continuous programme of improvement through customer feedback. Arthur is sufficiently enlightened to allow serious potential customers to test drive the demonstrator, although as an initial step, £1.50 will bring you an eight-page colour brochure to study.

Finally, I would like to thank our model, the delightful Laura Peacock. Laura, whose father lent us the Cessna, achieved the CCC award for bravery under canon-fire by enduring a very cold and lengthy photo-session without a single whinge.

…or Mysterious Maserati, False Ferrari or Imitation Itala. The Ronart W152 is the car you want it to be, as David Hill discovered.

(Reproduced from Component Car magazine. March 1989.)

Despite the aeroscreen, the flies stung like fury as they met their sudden end, their shattered remains mingling with those of their predecessors in the mask of oil and grime covering my face. Steel, blood and bone sped on at an insane pace as the two machines, their drivers urging them on as much by willpower as with skill, vied for supremacy at the last bend.

The bulbous tail of the blood red Ferrari rose a fraction as the brakes bit, the open exhaust spitting defiance at the closure of the throttle. This was my signal. Casting loose from the slipstream’s pull, I swung the car’s silver nose towards the inside. Foot down, snake, correct, drift… I was through and charging hard for the Finish. The welter of passing images held the memory of a momentary swoop of black and white checks. Onward to victory, champagne and the winner’s laurels.

Click to view a larger image.

The ability to weave such dreams is a rare quality in anything, let alone a mere means of transport, but the incredible Ronart had that ability down to a fine art. The day on which I tested the car was one of those during which the percentage of successful events is balanced by an equal percentage of opposing forces. Support cars broke down, people lost each other in transit; that sort of thing. Thus, schedules went awry, leading to test conditions that were less than ideal.

When I finally got around to driving the Ronart, it was late. The lateness of the hour, not to mention that of the season, meant that the temperature was well on the wrong side of zero, making black ice more than likely to be encountered. Also, it was pitch dark. By my reckoning, testing the ability of the Ronart to bounce off the scenery whilst in a zero grip slide was just a little beyond the call of duty. So the insane pace was, in fact, about 60 mph. The blood red Ferrari was a wayward Metro and the final curve was a roundabout somewhere outside Peterborough. Still, although the Ronart could not be tested either to my satisfaction or to your, it still had that magic quality. Let me explain why.

If you were to meet Arthur Wolstenholme socially, it would come as something of a surprise to learn that he produces such a car as the Ronart. The same goes for his wife Rona who, apart from making up 50% of the car’s name, plays a major part in the business, and is a dispenser of medicines to boot. Arthur himself is a RAF trained electronics engineer, a profession that he continues to pursue. Their house, with the exception of a few pictures, is devoid of the automotive trinkets usually encountered; in general, no clues to the way in which the Ronart project came about are to be found. However, judging books by their covers is a profitless occupation, the adage proven by that that came to light as the story unfolded.

In 1981, Rona and Arthur had a continental holiday, during which they visited the Mercedes Benz museum at Stuttgart. Arthur, studying the early racing cars on show there, wondered what it would be like to drive such a machine on the road. The Ronart was conceived with that thought and, on returning home, Arthur started to sketch. Naturally, the car would have to be a two-seater, for Rona’s benefit. And an initial design, complete with doors, was arrived at. 1984 saw the arrival of a dog-eared XJ12 in the Wolstenholme household and armed with the proposed body’s dimensions and a pile of parts mechanical, Arthur set about marrying the two with a chassis.

Click to view a larger image.

This was a box-section steel structure following a basic ladder pattern, put together in the garage with an arc welder. The string and chalk mark method brought together a chassis worthy of the name, but one which was neither pretty nor particularly efficient in terms of ration of strength to weight. Putting it bluntly, it was crude, and the pedantic Arthur wasn’t happy with it. But during this exercise, potential markets for the project had been studied, with the initial target being the classic car enthusiast. The concept was unique and apparently saleable, and so the decision to go into some serious development was taken.

In January 1985, Spyder Engineering was commissioned to put together a chassis suitable for V12 power and, at Arthur’s home, work started on a jig for an all-alloy body. The results of both these actions met up a few weeks before the NEC Motor Show in May, and the car made its debut there as a visual concept. The feedback from this appearance was tremendous, despite the car’s partially complete state. The public was taken aback and there were members of the Jaguar Drivers Club who were convinced that it was the Indianapolis Lister Monza car. On the second day of the show, the owner of that unique vehicle came over to the stand in a state of concern; he was worried that the Ronart was to be marketed as a replica of his car and needed a lot of reassurance that such a crime wasn’t to happen!

Click to view a larger image.

With exclamations of approval still ringing in their ears, Arthur and Rona took their car to the Kit Car Show at Newark. This appearance realised the possibility of marketing the Ronart as a kit car. The valid point was that, although the alloy body was a desirable commodity, the cost of producing it narrowed the market considerably. The existing body therefore served as a buck for a suit of clothes in GRP, the moulding work being carried out in the winter of 1985. The resultant body was mounted on the chassis for the 1986 Stoneleigh kit car show, and the car made a second appearance at the NEC shortly afterwards. By October the Ronart was roadworthy, and in November, five independent motoring magazines carried out tests. The Press were impressed and, encouraged by the response, Arthur continued the development work.

Click to view a larger image.

Over a 12-month period, a variety of spring rates and roll-bar thicknesses were experimented with, leading to a fully sorted suspension in the first production car which appeared in mid-1987. Earlier this year, the current production mould had been constructed, once again using the original body as a buck. The final result is lower, shorter and wider than the first GRP body, and countless hours of labour have brought about substantial improvements in the fit and finish of the panels. A number of potential customers drove the car, becoming actual customers in the process, so that 8 Ronarts now grace the Queen’s Highway, with a further 12 gracing the Wolstenholme order book.

Click to view a larger image.

The conclusion to be drawn from this history is simple. There has been a large amount of development, which is a costly process to say the least. The car could have been on the market in the early part of 1986. The fact that it wasn’t released until more than a year later proves that, in theory at least, the time and effort were taken to get the car right. Having encountered the fast buck approach in the past, I considered this painstaking approach to be praiseworthy. But would the Ronart live up to its on-paper promise? The investigation continued.

Arthur Wolstenholme and Victor Moore, director of Spyder Engineering are two of a kind. They are both men who know a great deal without making a noise about it. They let their work speak for them. This means the expectation of a highly finished product is a reasonable one.

Spyder’s experience in the manufacture of Lotus replacement chassis has been employed in the backbone item produced for the Ronart. This structure is well up to handling the power of the V12 and accommodating the straight-six XK engine is merely a matter of swapping mounting brackets. The chassis accepts Jaguar wishbones at the front, allied to Spyder’s own roll-bar and an MGB rack which makes use of extension couplers attached to Jaguar ball-joints. Spyder-developed steering arms are used which, like the optional Spyder front wishbones, are nickel plated to a fine finish. Apart from the visual aspect, this procedure makes any cracking easy to spot.

Jaguar’s independent rear suspension is attached to the chassis by metalastic bushed carrier plates, allowing the heavy and rot-prone Jaguar cage to be dispensed with. The only other modification is the attachment of special tie-bars which are sufficiently lengthy to avoid wind-up under cornering loads. Spyder also manufacture pedals and engine-mountings and those items which are not cadmium or nickel-plated are sandblasted, etch-primed and then given a baked enamel coating. The practical results are an excellent finish and a six-year anti-corrosion warranty.

One criticism of a backbone chassis is its lack of side intrusion protection. In the Ronart, shaped frames follow the body contour at the scuttle and rear bulkhead planes. Furthermore, each side of the cockpit is protected by a rail which is bonded into the body and bolts to the frames at either end. The complete structure is further employed in providing locations for the seat belts, pedals and steering column, and beneath the hump is a roll-bar extension to protect the driver’s head.

The rolling chassis is a relatively simple structure in itself. The comparatively light weight of the car allows the use of single rear dampers, and extraneous bracketry is conspicuous by its absence. The bodywork is formed in six sections, minimising the extent of replacement required in the event of minor crash damage. Space limitations dictate the use of a special radiator which employs a high-efficiency core capped with the original Jaguar tanks. A beautifully made alloy fuel tank is mounted in the tail protected by the rear-end hardware. The tank is fully baffled and is surmounted by a polished Aston-type fuel cap concealing the ‘real’ filler.

The braking system is transferred direct from the donor with the exception of the servo unit. The smaller Marina servo reduces the level of assistance to an amount suitable for the lighter Ronart, taking up less space in the process. The rearward siting of the engine necessitates a shortened propshaft which is available on an exchange basis. The associated extension to the steering column is provided in the shape of a bespoke steering shaft, while the magnificent exhaust system is also specially made but is not quite what it might seem.

A manifold and E-Type pattern silencers are made of mild steel. The pipes, wrapped in woven asbestos tape, live inside the flexible stainless covers which give the exhaust its visual impact. The punctured silencer cover is also in stainless steel. Inside the car, use is made of the Jaguar instruments and optional dashboards are available for XJ or S-Type clocks. The seats and trim are specialised items with the option of hide being available. Current weather equipment consists of a tonneau cover or alternatively a single-seat conversion panel in GRP. A wrap-around windscreen is currently being developed in perspex. A glass wrap-around screen and a hood and side-screen set will follow shortly.

A car such as the Ronart demands the use of wire wheels and these, and their associated hardware, are available from Ronart. Further traditional demands are satisfied by accessories such as a cast alloy spark-plug holder and spun alloy racing mirrors. Ronarts are available in left- or right-hand drive form and for the absolute purist, hand-made alloy bodywork may be specified. Part-builds are also undertaken upon request. Part-builds notwithstanding, the ease or otherwise of building a kit car is a major factor in its popularity.

A system of part identification for the Ronart has been generated with a computer. The result is a four-sheet list upon which each and every item is listed by description, size and quantity. Every single part has a reference number, that same number appearing on the bags and boxes in which the parts arrive. This has been done so thoroughly that, provided you can resist the temptation to open all the nags ta once, putting a Ronart together should be simplicity itself. Allied to this is a very comprehensive level of supply, down to the minutiae such as brake pipes, rack shims and battery clamps. The whole of the hardware is included in the kit, as are the siring loom and fuse box. The same goes for the special radiator and even the electric fan is included.

The advantage of this approach is a considerable one in that, given a good set of donor parts, no time need be wasted in motor accessory shops. It’s all there for you. The foregoing reveals the Ronart to be a desirable prospect in many ways. However, a manufacturer could go to the extent of including the paint in the kit and still not compensate for a basically poor product. This begs a question. How good is the Ronart in the flesh?

Visually I can think of nothing quite like it and if you like to be noticed this is the car to buy. The Ronart is also a sizeable device measuring 170″ from nose to tail, and standing back to take the car in as a whole requires a modicum of space.

A point that may be mooted is that the use of unmodified XJ6 suspension has dictated the overall size of the Ronart. Alternatively the generous legroom in the legthy footwells may be considered as either a cause or a result of the car’s size. What matters is that the car is proportionate, and if that makes it imposing, so much the better. The Ronart’s lines are curiously reminiscent of many different cars and according to Arthur, the colour used makes a big difference. Consequently, by sticking to the relevant national racing colour, you can have a reasonable representation of a Ferrari, a Jaguar, a Vanwall or whatever takes your fancy.

Unfortunately legal requirements must dictate a compromise in certain areas on such a car. Bolting lights and mudguards onto a racing car is bound to make it look odd, but it must be done. In the case of the Ronart, these items have been added in an unobtrusive way, and look as much at home as can be. Negotiating the low cockpit side to gain entry to the car was easy, only the bulk of the essential flying jacket hampering the entry procedure. Once installed, I found the cockpit comfortable despite the lack of carpets. Arthur had set the car up for himself but the position of the pedals in relation to the fixed seat was fine for me. Freaks of nature are provided for by a range of pedal fixing points, the use of which is a task requiring spanners.

The large, near-vertical wheel was sufficiently well spaced from both the dash and the driver to be comfortable and the side cutaway left plenty of elbow-room. The dash itself was a no-frills affair, with the required information and no more. Jaguar instruments were reasonably well-placed, with minimal masking by the wheel. The seats, dash and bulkhead roll trim was nicely done, although the tunnel trim was a touch wrinkly in places. The overall effect was simple, though not spartan, and therefore comfortable.

With the controls identified, I fastened the three-point harness and pressed the starter-button, to be rewarded by heavy churning noises from up-front. Next came the sort of sound which is capable of turning an enthusiast’s spine to jelly. The bark from the short side exhaust may not have been loud but it certainly sounded right with bags of basso profundo to be heard. The gearchange on the high tunnel too had a typically Jaguar feel as it was slotted (there is no other word) into first, and Arthur and I cruised forward into the cold darkness. At this point it was necessary to pass through an area used by adairy for the daily washing of their vehicles.

The concrete apron, which had be wet, was by now a solid sheet of ice and the start of the test consisted of mostly wheelspin. With this warning in mind, I set out onto the open road. The quality of the Ronart’s ride was noticed first, the rigid chassis and quality bodywork combining to give a supportive feel on the road. This created an immediate feeling of confidence and, with a long dual-carriageway to be used, the Hill hoof headed for the bulkhead. The reward for this action was a straight-six symphony accompanied by a firm push in the back.

The demonstrator was fitted with a 3.07 differential, giving a theoretical top speed of 180 mph! This tallness of gearing made its presence felt by reducing the acceleration from shattering to merely lusty. The 4.2 engine, breathing through triple 45 DCOE Webers on a Lynx manifold, was nevertheless fully capable of delivering the goods on demand and using the overdrive made top gear cruising a very relaxed procedure.

The numerous roundabouts in the area gave me the opportunity to explore the handling. The rearward siting of the engine gave the car a strictly neutral balance which, allied with the pin-sharp responses, made the Ronart more agile than might have been expected. In fact, given better conditions, I would say that flinging a Ronart through the bends would constitute one of life’s little pleasures. The controls offered a pleasing firmness, yet were light enough, I would image, for the ladies, given suitable modifications to the low seating position.

Driving the Ronart gives a unique view of the world, with seemingly yards of bonnet in front and a position knee-high to almost every other road user. The vision from the hot seat was good and the two scuttle-mounted mirrors gave a complete picture of event behind. When I enquired after heating facilities, Arthur gave me the sort of glance which suggests that great fairies are in mind. Despite that, a heater can be fitted, the Mini or Spitfire unit being the favourite choices. Apparently those Ronart owners who have a heater can be easily spotted: they’re the ones who are still grinning in sub-zero conditions.

Critics of the Ronart are apt to use the word ‘impractical’ with monotonous regularity. This is a reasonable enough view, although the recent innovation of a hingeing tail has provided a surprisingly capacious, if oddly shaped, luggage area. This apart, the Ronart must remain a superb cobweb-remover until the weather equipment appears. However, if your pocket will stretch to a car more suited to the Beaujolais Run than the weekly shopping trip, the Ronart is unparalleled in its appeal.

Two versions of the car are available, the S6 kit for the XK engine and the more obviously titles V12 kit. The basic body/chassis kit cost £2994 plus VAT in either case. The additional parts packs cast £3750 plus VAT for the S6 and £3950 plus VAT for the V12. The listed optional extras include such parts as seatbelts, tonneau cover, aeroscreens, wheel and hubs. Hide trim is also listed as an option to the standard leathercloth, with the possibility of mixing and matching trim materials to taste. Over and above the works items, you will need a donor, a set of tyres and an amount of paint,

These prices seem high at first glance. Whilst it is true that the Ronart is not a cheap kit, anyone who has had the experience of building a kit car will know how quickly the cost is boosted by those nuts, bolts and lengths of Aeroquip hose. If in doubt, try asking your local fabricator for a 6 into 1 exhaust in mild steel with stainless cladding. Furthermore, the inclusion of all the little brackets, painted and ready-to-use represents a valuable saving in man-hours alone. These, in common with the rest of the fabricated parts, are of the highest quality.

The comparatively simple nature of the Ronart’s construction would, I feel, make for an easy build and Arthur and Rona supply each builder with report forms to fill in, the aim being a continuous programme of improvement through customer feedback. Arthur is sufficiently enlightened to allow serious potential customers to test drive the demonstrator, although as an initial step, £1.50 will bring you an eight-page colour brochure to study.

Finally, I would like to thank our model, the delightful Laura Peacock. Laura, whose father lent us the Cessna, achieved the CCC award for bravery under canon-fire by enduring a very cold and lengthy photo-session without a single whinge.